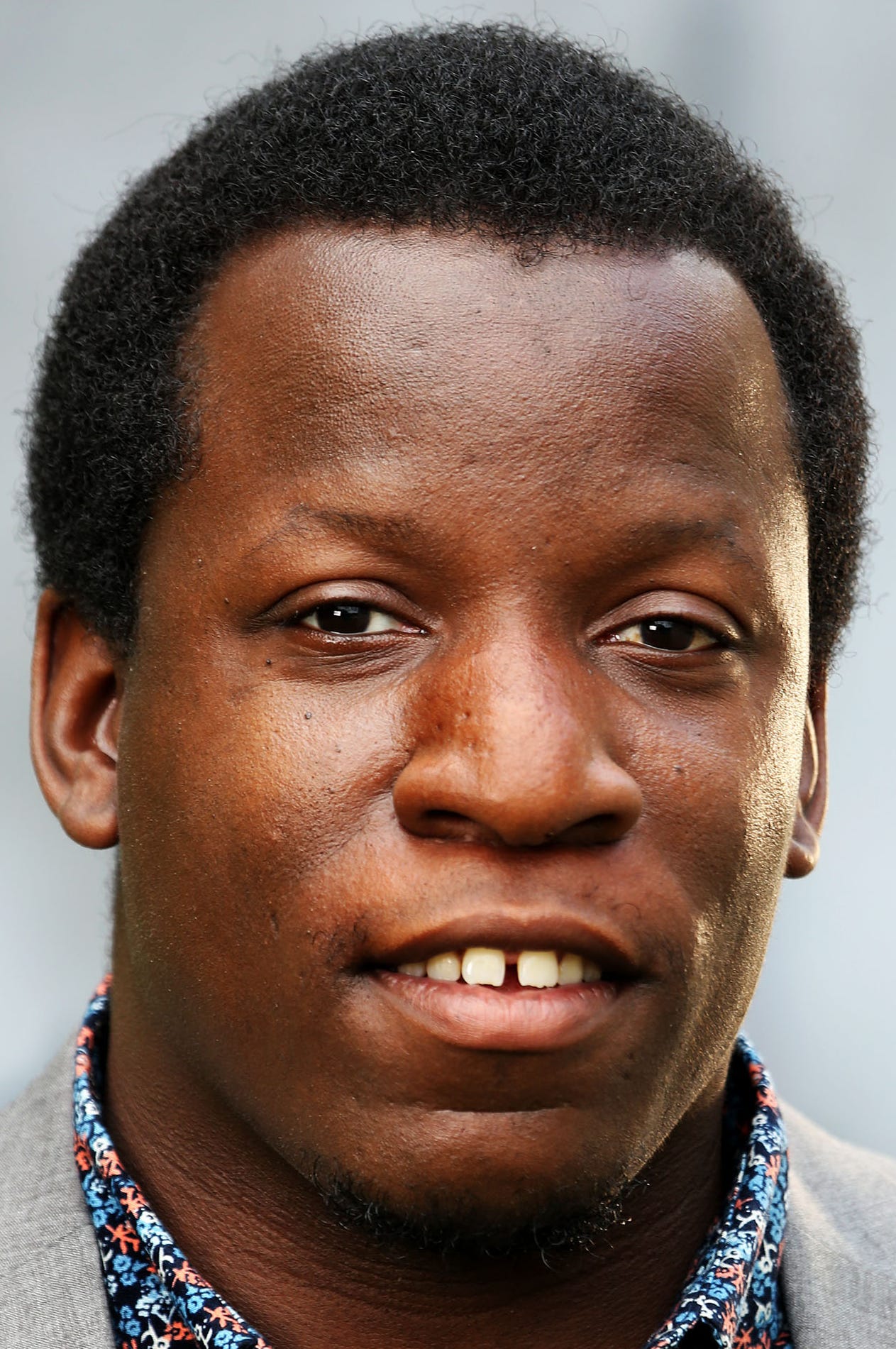

Jeremy Triblett was 16 years old when he experienced one of the most transformative moments in his life.

As a junior at the Milwaukee High School of the Arts, he joined the youth leadership program Urban Underground at the urging of a friend. In September 2007, the organization took Triblett and dozens of other teens, predominantly African American, on a retreat two hours north of Milwaukee. For most, it was their first trip outside the city.

The goal was to give the teens a sense of their shared history, so they could understand the sacrifices made by those who came before them. On the first night, while the teens were relaxing under the stars, organizers rounded them up and blindfolded them.

Lined up single file, they were told to place one hand on the shoulder of the person in front of them, and remain silent.

Deep in the woods, the blindfolds were removed and flashlights shined in their faces.

“Welcome to America,” someone said on the other side of the flashlight.

“We were on an auction block,” Triblett said. Just like the millions of Black men, women and children who were stolen from Africa to be enslaved in America.

Angela Peterson / Milwaukee Journal Sentinel

The exercise, though jarring, showed the teens that the journey for people of color started long before their experience. Generations before them paved the way and made sacrifices, Triblett said.

“Our ancestors were stronger than the chains that bound them. Their spirit and fight exist in me. Do you understand how powerful that is?” said Triblett, who went on to found his own company specializing in youth training and professional development.

By setting up that exercise and many others, Urban Underground pointed its members toward a larger goal: engaging in their schools and community, and developing a deeper understanding of who they could be and how activism can spark change.

The idea is to allow teens to speak openly with peers about the things they see every day — crime, reckless driving, violence — and give them tools to create programming necessary to change those conditions.

Urban Underground exposes youth to possibilities that many of them may not ever have considered. It shows them what’s possible.

“I say it to this day: Urban Underground was one of the most transformative organizations out there, because it was during my time with them that I knew that activism is what I wanted to do,” Triblett said.

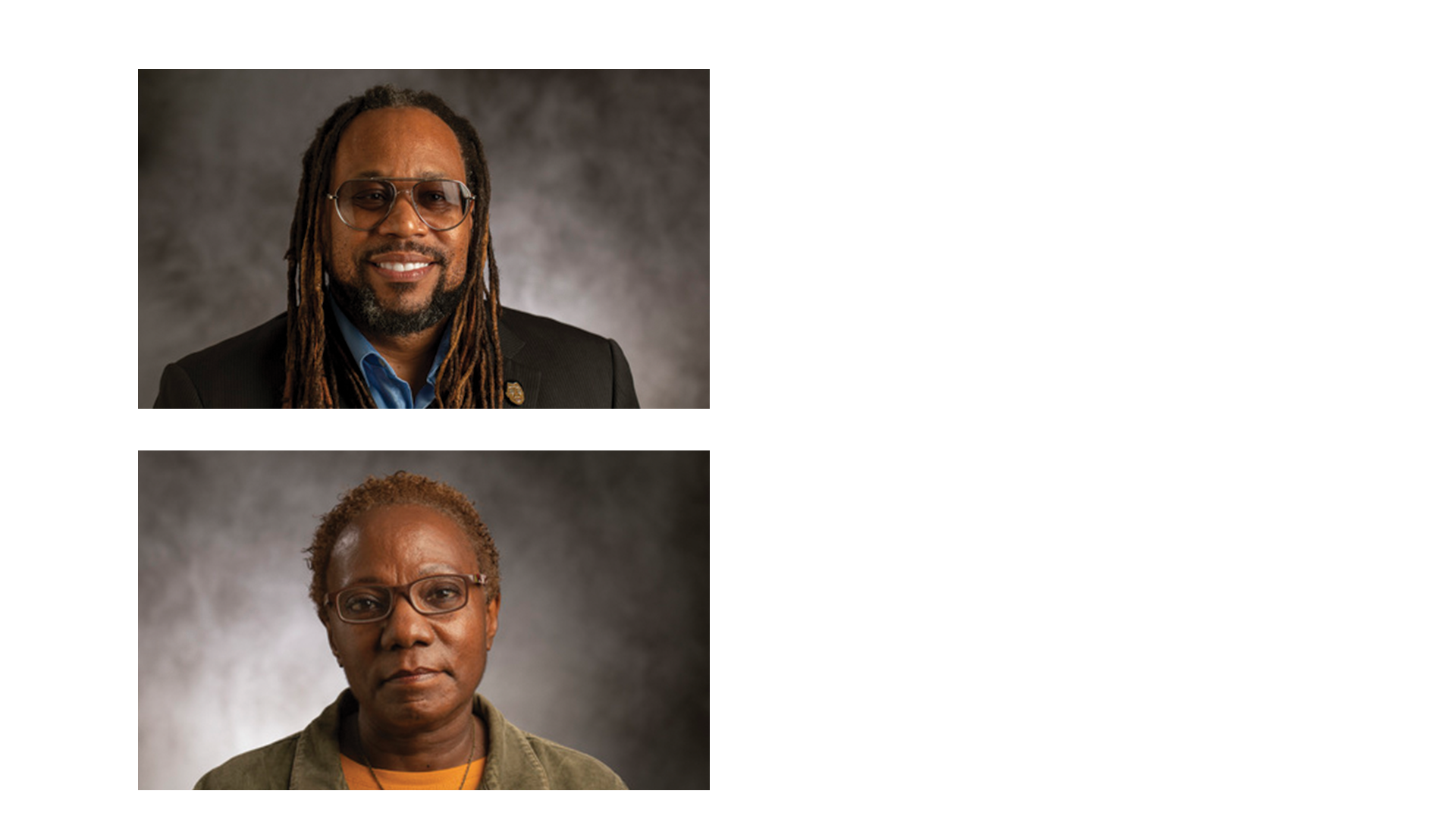

Reggie and Sharlen Moore started Urban Underground in 2000 as a way to impact young people of color by offering life skills workshops.

“Milwaukee is a tough place to live and we wanted to make sure that our young people were equipped with the skills to cope,” said Sharlen Moore, the executive director, with more than 27 years of experience with young people

Angela Peterson / Milwaukee Journal Sentinel

After political leaders struggled to come up with solutions to curb Milwaukee’s cruising problem on the city’s northwest side in 2000, Urban Underground organized discussions, many led by young people. The result was a youth-led signage campaign. The cruisers listened because the message wasn’t coming from adults, it was coming from peers whom they respected.

Too often, teens feel overlooked and undervalued, Moore said. It doesn’t help that recreational opportunities have disappeared, summer jobs and internships are scarce, and neighborhood-based arts and cultural programs have faded.

Urban Underground differs from other programs in that it places youths front and center, said her husband, Reggie Moore, now the director of violence prevention policy and engagement at the Medical College of Wisconsin.

“I’m not judging other youth programs, but Urban Underground exists because we wanted to see our young people, not hide them,” he said.

If there’s a spike in youth crime or violence, adults say, “We have to create a program to get youth off the street,” Moore said.

Taking them off the street to play basketball for a few hours doesn’t get to the root causes.

“Our youth know when a program is designed just so they don’t have to be seen or heard,” Reggie Moore said.

Young people want and need to be engaged, and if you don’t teach them their worth so they can become leaders, then the problem never goes away, he said.

Joining Urban Underground, which typically recruits at high schools during lunch, is easy. A person must be between 13 and 18 years old; tired of the violence in their school and neighborhood; open to connecting with new people from different schools; and ready to be a difference-maker. Every student goes through an interview process, but if a youth is motivated to make change in their community, they are not turned away.

The organization’s work reflects critical consciousness theory — the ability to recognize and understand inequality and the commitment to take action to dismantle the systems that encourage oppression. It goes hand-in-hand with critical race theory, which has received a great deal of attention in political and education circles lately. Critical race theory is an academic examination of whether systems and policies perpetuate racism. For all the controversy, it is generally accepted as an obvious truth in communities of color.

A 2019 University of Illinois-Chicago report showed how researchers attempted to measure how low-income, minority youths put the critical consciousness theory into action. In the report, researchers asked a pool of Chicago youths ages 13-17 which issues most commonly impact them. About three in five said community violence; about three in 10 said prejudice and intolerance.

When asked to participate in solution-based activities to address these issues, 65% of the youths participated in at least one activity over a six-month period. In other words, when given the opportunity to be part of the solution, nearly two-thirds of the teens said yes.

“Our youth are some of the most incredible young people out there. When we cultivate them, the leadership comes out,” Sharlen Moore said.

Involved young people don’t jump into stolen cars, drive reckless, fight in their neighborhoods or commit many of the crimes we often hear about. Involved young people build and get others to join them, she said.

One of the most gratifying honors Urban Underground leaders said they receive is when alumni send their children through the program.

While Triblett’s child is too young to join Urban Underground, he did get his nephew involved.

“He used to bring me into the office and let me play around on the computers and stuff. I really look up to my uncle, so when the opportunity opened up for me to join, I did,” said Jamire Carpton, 17.

Carpton, an 11th grader at Milwaukee Excellence Charter School, said he had the most fun last summer working with other teens on an environmental excavation team. The group looked for invasive plant species in the woods and eliminated them.

“It was definitely something that I never thought I could see myself doing. I learned a lot,” he said.

It was a change from previous summers.

“I mostly just spent time in the house eating and playing video games,” he said. “This was the first summer where I can say it was productive.”

Carpton said the biggest surprise came when he received a check paying him $11 an hour for his work.

Angela Peterson / Milwaukee Journal Sentinel

“I didn’t even know I was going to get paid. I would have worked for them for free. If any kid out there is thinking about joining, I would say just do it,” Carpton said.

Urban Underground counts among its alums state Rep. David Bowen and Milwaukee County Executive David Crowley. But Reggie and Sharlen Moore said they are most proud of the “everyday” people who have come through.

People who are leaders in their church. People running block watches. People raising strong families. People involved in mentorship programs.

“Impact can be made in many ways,” Sharlen Moore said.

“We just have to keep embracing our young people and giving them the real skills they need to be successful,” she said. “That’s all we try to do.”

To sign up for Urban Underground, go to urbanunderground.org/join.

Published

11:27 am UTC Apr. 25, 2022

Updated

11:49 am UTC Apr. 25, 2022

from WordPress https://ift.tt/4o2f1uS

via IFTTT

No comments:

Post a Comment